Building a New Fire: Reflections from the Repatriation Conference

Ashleigh and Shannon at the 9th Annual Repatriation Conference hosted by the Citizen Potawatomi Nation at the Grand Casino Hotel and Resort, Shawnee.

From November 7–9, 2023, the Save History team attended the 9th Annual Repatriation Conference hosted by the Association on American Indian Affairs and the Citizen Potawatomi Nation in Shawnee, Oklahoma. Attendees included Tribal leaders, institutional representatives, government employees, and cultural resource staff from across the United States, Canada, and even internationally.

In the following blog, two of the Save History staff share their experiences at the conference.

Ashleigh’s Highlights

Before driving to Shawnee, Shannon and I visited the First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City. The museum oriented us by providing information on the 39 Tribes of Oklahoma. I particularly enjoyed the “OKLA HOMMA” exhibit, which was curated by an all-Indigenous staff. The exhibit shares tribal origin stories, the history of colonialism, an overview of Native sports and athletes, and much more from the diverse Tribal Nations that call Oklahoma home.

Reservation Dogs mural by Anishinaabe artist Blake Angeconeb at the First Americans Museum, Oklahoma City.

We also had the opportunity to tour the Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Center in Shawnee, Oklahoma. The Potawatomi, Ojibwe, and Ottawa are all Anishinaabe and make up the Three Fires Confederacy. As an Ojibwekwe, it was interesting to see the similarities between the Potawatomi and Ojibwe languages and cultures. In addition, I learned how the Potawatomi were removed so far from their homelands in the Great Lakes region.

There were many compelling stories at the conference about the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) and efforts by Tribes to return their Ancestors and cultural items. One of my favorite sessions was “Preparing to Bring Our Ancestors Home: Rematriation of the Wilps Ni’isjoohl Memorial Pole from Scotland to Nisga’a Lands.” The Ni’isjoohl memorial pole was stolen from the Nisga’a and sold to The National Museum of Scotland. This year, the community was successful in bringing their memorial pole home.

Shannon’s Highlights

My second visit to the museum was just as engaging as the first! I visited back in May during an ARPA training we taught with the BIA Indian Police Academy. I spent a long time in the WINIKO: Life of an Object exhibit, in awe of the artistry and cultural significance of the materials on display. An Indigenous curation team led the return of these belongings, taken by ethnographers who exploited Tribes in Oklahoma in the early 1900s. I was moved by the videos, which shared the families’ emotional experiences when their ancestors’ cultural materials were returned.

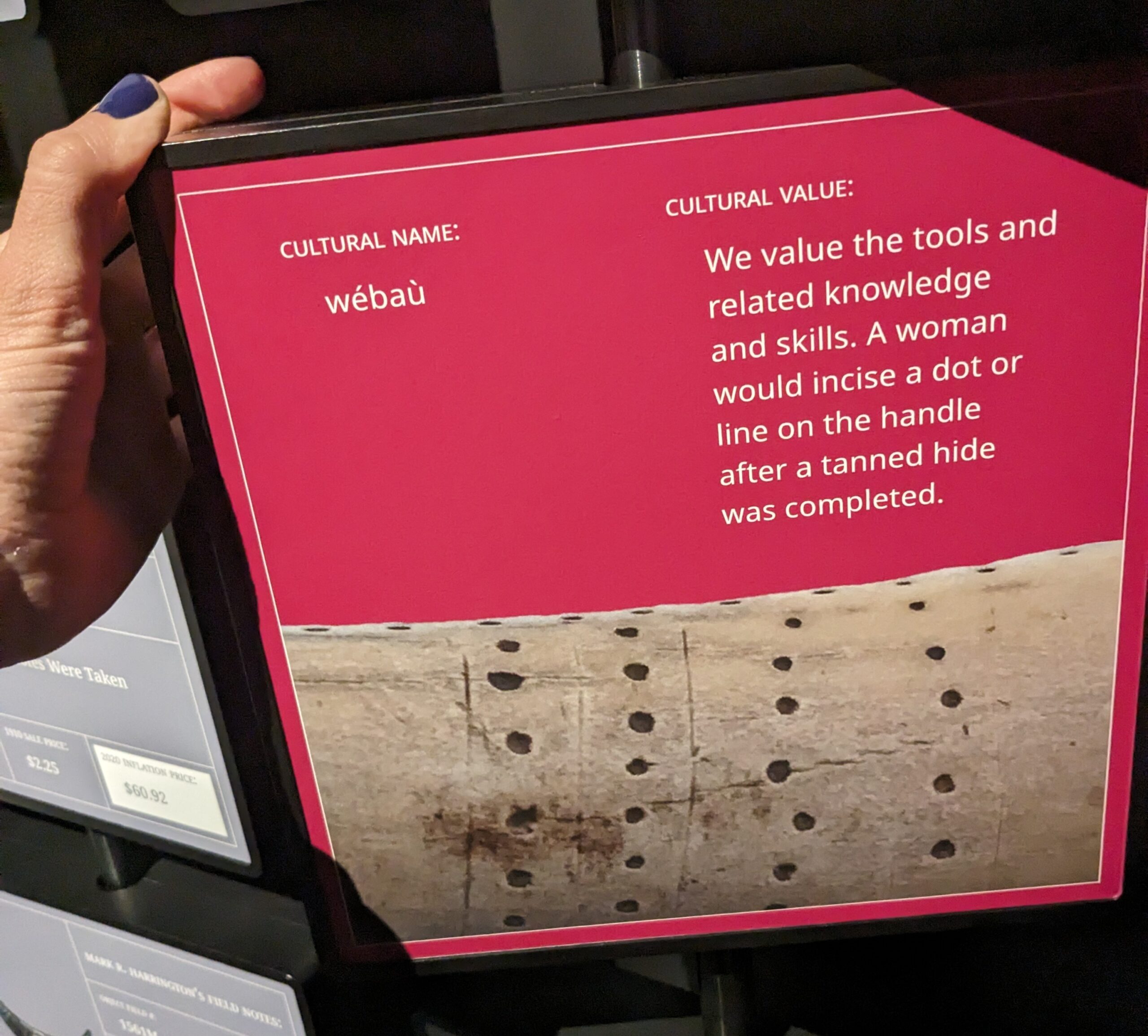

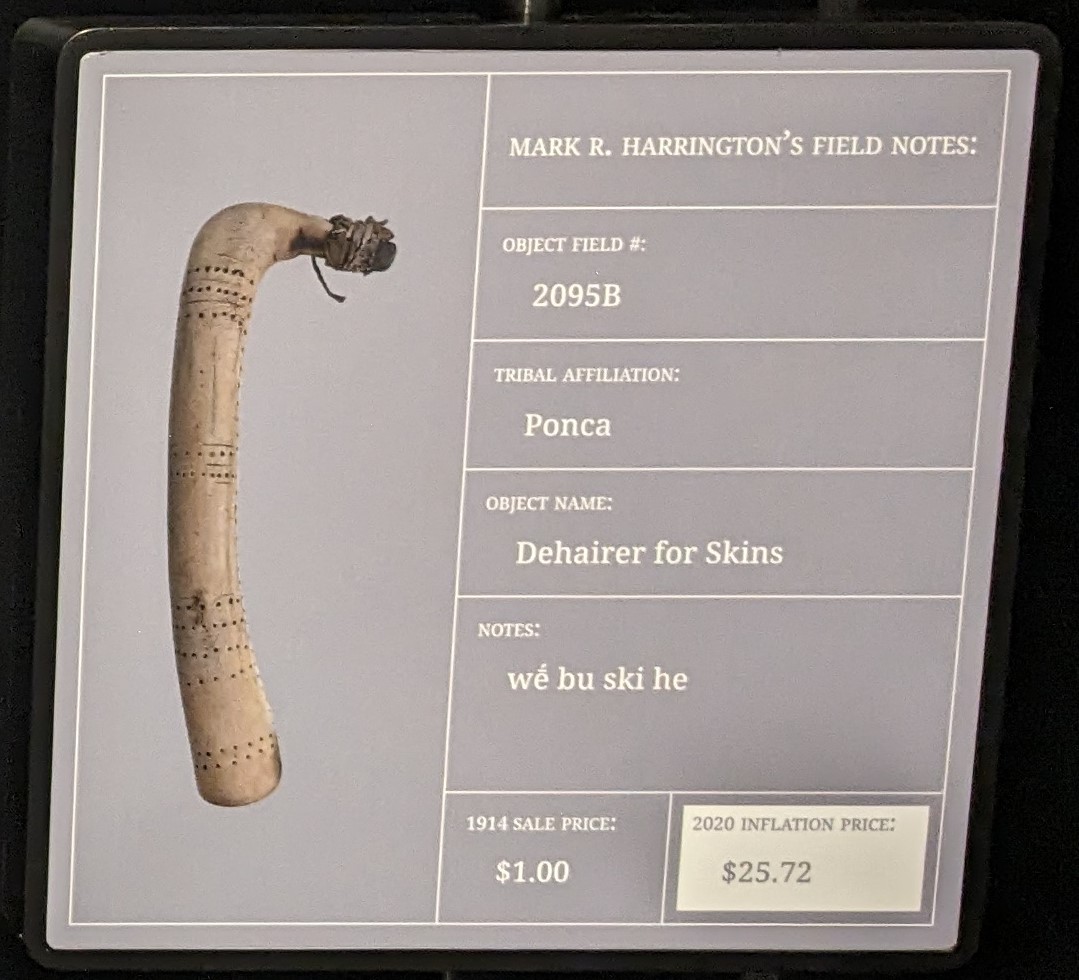

One part of the exhibit that stood out to me contrasted the cultural values held by Native people versus white collectors. Unfortunately, the values of those collectors still exist today, supporting a cash-based market for cultural items. We hope to change these attitudes through our site protection work, and we share similar stories about Indigenous values of respect and protection of cultural sites.

Indigenous cultural values (left) versus settler colonial values (right). IMAGE: WINIKO: Life of an Object. First Americans Museum, Oklahoma City.

I learned a lot from the first conference session: Advocating With Our Stories: Journalists Discuss Investigating NAGPRA Compliance. I admired the journalists’ ethics and their skill in building trust with Indigenous communities, who have often been exploited or re-traumatized by investigative reporting. It’s exciting to witness a cultural shift in journalism, museums, and archaeology toward storytelling for and by Indigenous people. Instead of focusing on trauma, these journalists hold institutions accountable, explore why power imbalances persist, and tell stories of change.

Read more: The Repatriation Project, ProPublica

One audience member at the conference described 20th-century archaeological collections as part of a trade network between white men, whose motives, monetary gains, credentials, and legacy are only now being called into question. The “founding fathers” of ethnography and archaeology caused so much harm through theft.

In contrast, Ashleigh and I noticed that over two-thirds of the conference participants were women. During the final presentation, Dr. Amy Parent (Nisga’a, Associate Professor at Simon Fraser University) commented on how Nisga’a Matriarchs and women from the National Museum of Scotland stepped forward first to build relationships and support the rematriation. Dr. Parent also shared her internal debate about whether to name the man who took the Ni’isjoohl Memorial Pole–a so-called expert in ethnographic research who nonetheless stole a significant cultural belonging.

I think a lot about how remediation work in museums, archaeology, and Tribal cultural preservation can be gendered: literally, many of us are cleaning up horrific messes left by people who will never be held responsible. I find this challenging yet so important, and this is why our archaeological site protection work feels like a personal and cultural responsibility to me.