White Mountain Apache Perspectives on Protection and Healing at Ancestral Sites

Ndee (Western Apache) communities often avoid ancestral sites and places associated with the past out of respect. Ndee communities demonstrate such respect in the form of avoidance to protect both community members and archaeological sites from potential harm. Most importantly, avoidance helps maintain Gózhó, a state of balance and harmony in the world.

However, desecration, looting, and graverobbing of ancestral sites by non-Ndee individuals is a serious problem on White Mountain Apache Tribal trust lands. Past archaeological research on the Fort Apache Reservation has also been invasive and extractive. Archaeologists have removed thousands of cultural items and ancestors from multiple sites on the reservation. Due to sustained Tribal leadership over the past twenty years, repatriation efforts have led to the return of the vast majority of human remains and funerary objects, with the remaining ancestors soon to be returned. Both looting and archaeological excavations have disrupted the balance of Gózhó, bringing harm to the local Apache community’s health, security, and well-being.

Mark Altaha, Tribal Historic Preservation Officer, and Nicholas Laluk, Deputy Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for the White Mountain Apache Tribe (WMAT), sought to remedy this imbalance by organizing a community-based restoration project at a hard-hit village site. They hope this will evolve into a collaborative, tribally-driven archaeological field school where students learn Archaeological Resources Protection Act damage assessment and restoration techniques including tribal cultural heritage best management practices and least impact archaeological methods.

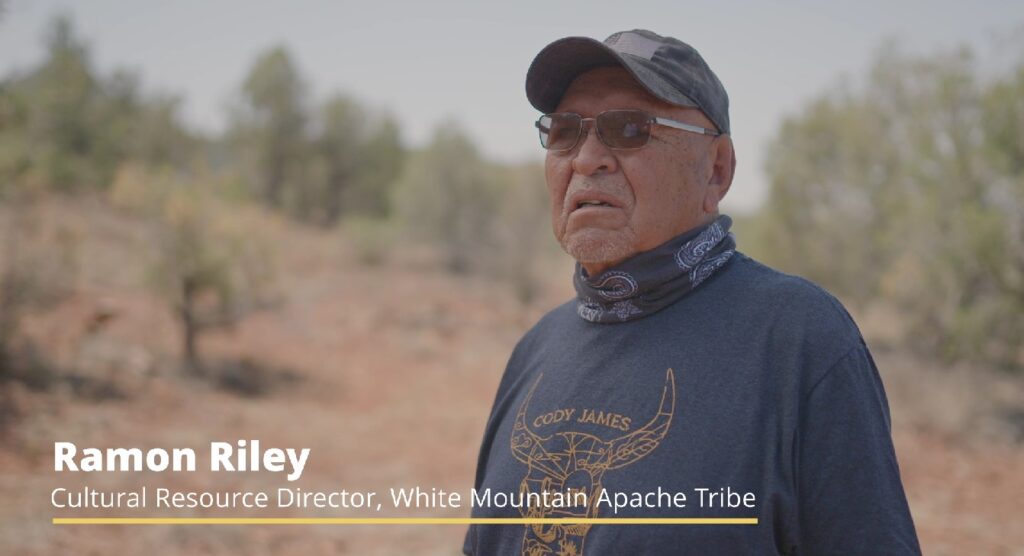

As part of the 2021 pilot project, the Save History team interviewed Dr. Laluk and two Ndee Elders and cultural heritage experts: Ramon Riley, Cultural Resource Director for the White Mountain Apache Tribe, and Benrita “Mae” Burnette, Cultural Resource Heritage Expert for the White Mountain Apache Tribe.

You’ll notice that we don’t share the site name or location, and we have carefully avoided showing any landmarks in these videos. Keeping the site location secret, especially when sharing photos or videos on social media, helps prevent future looting and vandalism.

Protection and Prayer Before Visiting Archaeological Sites

Ramon Riley discusses how respecting the land is crucial for survival and good health. In both Apache and English, he describes how Elders warned him of the dangers of visiting archaeological sites or touching ancient tools. Smudging and other protection strategies can protect those who visit or work at sites. Mae Burnette echoes these sentiments and shares how she uses blessings like the application of hádńdín (cattail pollen) to protect herself and the THPO crew.

White Mountain Apache workers were hired to excavate and restore Kinishba Pueblo in the 1930s. Despite their cultural practice of avoidance and concerns about death disease, they accepted these jobs because there were no other local opportunities. They too prepared themselves with prayers and blessings. Pre-project blessings set the tone and create balance so the crew can go into work with a good mindset.

“If you go to someone’s house, you don’t just barge in. There’s protocols on what you have to do.” (Ramon Riley)

Protecting Archaeological Sites from the Heart

Mae Burnette talks about the ancestors who lived at the site and their understanding of the landscape. She also discusses the role of springs and the importance of water resources near ancient sites. She explains how she thinks of archaeological sites as homes that protect their inhabitants—and how we need to protect these ancient homes and the teachings they can share with us. Ms. Burnette describes the emotional impact of reburying an infant that was taken by archaeologists from Grasshopper Pueblo.

“You know, we got all the pleasures. We got indoor plumbing and they didn’t. We got a swimming pool where we can cool off. But they didn’t. We have all the pleasures while they didn’t. So the way I see it is that right now, we should at least try to protect them, protect the site.” (Mae Burnette)

Causes and Effects of Looting and Theft

Looters are motivated by profit and steal from many sites on WMAT land. Intergenerational looting traditions are an ongoing issue, especially in nearby towns just outside the reservation where people learn to loot from parents and relatives. Looters may still be scouting on WMAT lands, so it’s important to monitor sites for signs of recent looting or trespassing. Stealing from sites can backfire on looters, inviting harm and imbalance into their lives.

Theft and desecration have profound impacts on the White Mountain Apache Tribe. Ramon Riley explains how history is stolen and erased by these acts. All objects at sites were made with prayer and ceremony, and are still the belongings of the people who made them. Restoring sites, preserving objects in place, and bringing home ancestors and their belongings can restore Gózhó.

Trowels

In this short clip, Nick Laluk discusses the differences between the toolkits Ndee people and archaeologists use to interact with sites. He talks about valuing Mae Burnette’s knowledge as an Elder and cultural heritage expert on an equal level with archaeological knowledge.

Restoring Balance after Destruction

Both archaeologists and looters can be referred to as ch’ndn in Apache—witches or devils who disturb the possessions of deceased persons. The 30-year-long archaeological field school at Grasshopper Pueblo removed hundreds of ancestors and their belongings, and the repatriation of those ancestors helped heal and restore communities living nearby. Archaeology doesn’t have to be destructive, especially when Ndee cultural values inform protection and preservation at sites. Repairing land disturbed by looters restores balance and protects Nígosdzán (Mother Earth).

“I don’t ever excavate, usually, but I’m still an archaeologist, and I still practice my cultural tenets in the ways I think are appropriate to allow us to move forward in preserving and protecting the past.” (Nicholas Laluk)

Credits

Special thanks to Mark Altaha and the White Mountain Apache Tribal Historic Preservation Office

Commentary by Nicholas Laluk (Deputy WMAT-THPO and Assistant Professor at the University of California Berkeley), Benrita “Mae” Burnette (Cultural Resource Heritage Expert for the WMAT), and Ramon Riley (Cultural Resource Director for the WMAT)

Interviews by Skylar Begay (Archaeology Southwest)

Edited by Victoria Rendon (Bicktorious Media)

Blog post by Shannon Cowell and Nicholas Laluk